For most of human history, the average lifespan hovered around forty years. Many lives ended almost as soon as they began—at birth or within the earliest years of childhood—while those who made it past these perilous stages generally navigated adolescence and early adulthood in relative safety. They endured injuries and diseases in harsh environments, and those fortunate enough to survive long enough often helped raise the next generation. Although our ancestors were physiologically capable of reaching old age, the realities of their world frequently cut their years short.

Paradoxically, as we transitioned from hunter-gatherers to farmers, and eventually to factory workers, we introduced more threats to our well-being than safeguards. Polluted air, processed foods, questionable drinks, and an assortment of inhaled toxins all played a part in shortening lives. For a time, humankind suffered the worst of both worlds: high infant mortality reminiscent of our ancient forebears, coupled with the modern, man-made causes of death arising from our new lifestyles.

Around the turn of the 20th century, we began to clean up our urban environment through improved hygiene and sanitation, bolstered by the development of antibacterial medicines. This one-two punch dramatically lowered infant mortality and increased life expectancy at birth. However, it did little to extend the upper limits of human longevity—our maximum possible age. Even today, despite living longer on average, improvements in life expectancy past our mid-seventies remain modest. It seems that for every stride forward, a new setback emerges. Many of the diseases we face as adults today didn’t exist centuries ago, implying that our modern world carries hidden costs.

As we “cure” one condition, we buy ourselves time only to face the next ailment waiting in the wings—some of which are byproducts of our own ingenuity. These obstacles form a gauntlet of sorts, testing us as we push for longer lives. The encouraging news is that, broadly speaking, problems of our own making are often solvable by our own hands. Each new disease or risk factor presents an opportunity to reshape our environment and to further refine what it means to live—and thrive—well into old age.

|

| Longevity Rates Since 1840 |

The Gauntlet

The gauntlet refers to the series of life-threatening challenges humans have faced for as long as we’ve walked the Earth. For most of our history, these dangers appeared early—often at birth or even before—and loomed large throughout infancy. Children who survived then enjoyed a brief reprieve in late childhood and early adulthood, only for the gauntlet to return in their late 30s or 40s. By then, years of wear and tear in harsh conditions often proved fatal. Simply making it to grandparenthood was a significant achievement; seeing great-grandchildren was virtually unheard of.

Today, the gauntlet has changed form. We’ve nearly conquered the childhood mortality that once claimed so many lives, and we’ve discovered ways to extend life spans well beyond those of our ancestors. Unfortunately, this progress has come with a host of new threats—many of them linked to modern lifestyles and habits. These are the new obstacles we must confront in our updated gauntlet.

The good news is that most of these threats are preventable, and in many cases even reversible, through changes in how we live. For some, these changes may be minimal; for others, they may be dramatic. But in every case, transformation is possible—and the payoff can be years, if not decades, of healthier, more fulfilling life.

Diseases of Childbirth, Childhood, and Adolescence

"The overarching hypothesis is that our bodies evolved within a highly active context, and that explains why physical activity seems to improve physiological health today." - University of Arizona anthropologist David Raichlen

In 1900, pneumonia and influenza, tuberculosis, and enteritis with diarrhea topped the list of causes of death in the United States, with children under five accounting for 40 percent of fatalities from these infections (CDC, 1999a). Today, only pneumonia (combined with influenza) remains in the top ten causes of death overall or for children, and deaths from infectious diseases among American children under five have been virtually eradicated.

After age five, accidents and, tragically, homicide become the most common causes of death. As individuals enter adolescence, personal behaviors—such as diet, exercise, smoking, and alcohol consumption—begin to play a larger role in mortality. Until our 30s and 40s, the leading causes of death are largely determined by the choices we make and the environment shaped by those around us.

Diseases Throughout Middle Age

As individuals move beyond middle age, mortality rates begin to accelerate dramatically, with death rates more than doubling compared to the previous age group. By the time people reach 65, the ranking of leading causes of death shifts noticeably. Heart disease and cancer exchange their positions at the top of the list, while chronic respiratory and cerebrovascular diseases suddenly rise into the top five.

Alzheimer’s disease also makes a significant entrance among the top ten causes of death, displacing diabetes and climbing to the number five spot. This shift highlights how the health challenges that emerge later in life differ markedly from those experienced at younger ages, underscoring the importance of targeted interventions and ongoing care as we age.

“A large body of research shows that one’s aging trajectory is largely determined by how we are in middle age. Those with lower blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, blood glucose, and body-mass index (BMI) in the forties and fifties, the study found, stood a much better chance of living to age eighty-five without any major health problems.”

Cancer

Cancer remains one of the most formidable health challenges of our time. It is not a single disease but a collection of more than a hundred distinct conditions characterized by the uncontrolled growth and spread of abnormal cells. Advances in medical science have led to improved detection tools and more effective treatments; however, the overall incidence of cancer continues to rise, partly due to aging populations and lifestyle factors that increase risk.

Lifestyle choices, such as smoking, poor diet, and physical inactivity, contribute significantly to the development of many cancers. Environmental exposures—ranging from pollution to harmful chemicals—further elevate individual risk, while genetic predispositions add another layer of complexity. Preventive measures such as regular screenings, adopting a healthy lifestyle, and early detection can all help reduce the impact of cancer, offering hope for better outcomes and improved survival rates.

Heart Disease

Heart disease stands as the leading cause of death in many parts of the world, underscoring the critical importance of cardiovascular health. Conditions such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, and arrhythmias have deep roots in both genetic predispositions and lifestyle choices. Historical patterns show that changes in diet, physical activity, and overall lifestyle have dramatically shifted the prevalence of heart conditions compared to earlier times.

Modern lifestyles characterized by high cholesterol, high blood pressure, obesity, and chronic stress place significant strain on the cardiovascular system. Diets rich in processed foods and unhealthy fats, combined with sedentary habits, further exacerbate the problem. However, many cases of heart disease are preventable through dietary modifications, regular exercise, stress management, and medical intervention. With the support of modern medicine—ranging from medications to surgical procedures—individuals can take active steps to manage their heart health and improve their quality of life.

Liver Disease

Liver disease often does not receive as much public attention as other chronic conditions, yet it represents a significant threat to overall health. The liver plays a vital role in detoxification, nutrient metabolism, and storage of essential vitamins and minerals. Diseases affecting this critical organ, whether from viral infections like hepatitis, excessive alcohol consumption, or metabolic issues such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, can severely disrupt bodily functions.

Many forms of liver disease are closely linked to lifestyle choices. Chronic alcohol use remains a major cause of cirrhosis, while the increasing prevalence of obesity has contributed to a surge in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Both conditions highlight how dietary habits and physical inactivity can impair liver function over time. Regular medical check-ups, moderation in alcohol consumption, and a balanced diet are key to preventing and managing liver disease, providing opportunities to maintain better liver health throughout life.

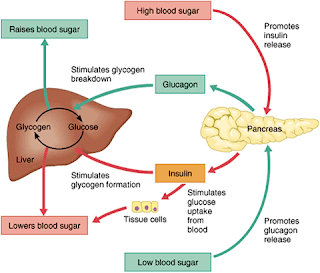

Diabetes

Diabetes is a critical condition that affects how the body regulates blood sugar, with profound implications for overall health. Type 1 diabetes is often linked to genetic or autoimmune factors and typically emerges early in life, while Type 2 diabetes—making up the majority of cases—develops gradually due to lifestyle influences such as obesity, sedentary habits, and poor dietary choices. The increasing prevalence of Type 2 diabetes reflects modern shifts in nutrition and activity levels across the globe.

Persistent high blood sugar levels can lead to severe complications over time, including damage to blood vessels and nerves, increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and kidney failure. Its subtle onset means that many individuals may not recognize the condition until complications have already begun to develop. This makes early detection and ongoing management crucial.

Fortunately, diabetes management is well-supported by both lifestyle changes and medical interventions. A balanced diet rich in whole foods, regular physical activity, and careful monitoring of blood glucose levels are essential in controlling the disease. In addition, medications—including insulin therapy—play a pivotal role in maintaining healthy blood sugar levels. Through these efforts, individuals can mitigate the risks associated with diabetes and improve their overall quality of life.

Diseases After Middle Age

After middle age, mortality rates begin to climb dramatically, with the human mortality rate roughly doubling every eight years compared to the previous age group. By the time individuals reach 65, the leading causes of death undergo a significant shift—heart disease and cancer exchange their positions as the top killers.

In addition, chronic respiratory and cerebrovascular diseases emerge unexpectedly, quickly ascending into the top five causes of death. Alzheimer's disease also makes a notable entry into the top ten, surpassing diabetes to secure the number five spot, highlighting the evolving nature of health challenges as we age.

Chronic Respiratory Disease (COPD)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive lung condition characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation. Primarily caused by long-term exposure to harmful particulates or gases—most notably from cigarette smoke—COPD encompasses emphysema and chronic bronchitis. This condition gradually diminishes lung function, making it increasingly difficult for patients to breathe. Environmental pollutants and occupational hazards can also contribute, further complicating its prevalence worldwide.

Managing COPD requires a multifaceted approach aimed at reducing symptoms and slowing disease progression. Treatments include bronchodilators, steroids, and oxygen therapy, along with pulmonary rehabilitation to improve overall fitness and respiratory efficiency. Preventive strategies, such as smoking cessation and reducing exposure to pollutants, are essential to curbing the onset of COPD. In addition, ongoing research is exploring new therapeutic avenues to enhance quality of life and extend the functional years of those affected by this chronic respiratory condition.

Cerebrovascular Disease (Stroke)

Cerebrovascular disease, particularly stroke, occurs when blood flow to a part of the brain is interrupted, either due to a blockage (ischemic stroke) or a rupture of a blood vessel (hemorrhagic stroke). This interruption leads to the rapid death of brain cells, resulting in varying degrees of physical and cognitive impairments. Strokes are a leading cause of serious long-term disability and remain a significant public health concern due to their sudden onset and potentially devastating outcomes.

Prevention and prompt treatment are crucial in reducing the impact of strokes. Controlling risk factors—such as high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, and smoking—is essential for lowering stroke incidence. Emergency medical care, including clot-dissolving treatments for ischemic strokes and surgical interventions for hemorrhagic strokes, can greatly influence recovery outcomes. Moreover, post-stroke rehabilitation plays a vital role in helping patients regain lost functions and improve their quality of life, highlighting the importance of comprehensive care from prevention to recovery.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects memory, thinking, and behavior. It is the most common cause of dementia, characterized by the accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain, which disrupt neural communication and lead to cell death. As the disease advances, individuals experience increasing memory loss, confusion, and changes in personality and behavior, ultimately losing the ability to perform everyday tasks independently.

The impact of Alzheimer’s extends beyond the patients themselves to their families and caregivers, who often face significant emotional and financial challenges. While there is currently no cure for Alzheimer’s, various treatments can help manage symptoms and slow progression. Pharmacological interventions, along with lifestyle modifications—such as regular physical exercise, cognitive stimulation, and social engagement—are recommended to maintain cognitive function for as long as possible. Ongoing research aims to uncover the underlying mechanisms of the disease, with the hope of developing more effective therapies and, eventually, a cure.

Frailty and The Fall

Frailty is the gradual loss of strength, speed, and energy that erodes our independence as we age. This decline not only increases susceptibility to infections and illnesses that often require hospitalization, but it also raises the likelihood of falls and disabilities. Research conducted on older adults has shown that frailty can double the risk of surgical complications, prolong hospital stays, and increase the odds of needing assisted living by up to twenty times after a surgical procedure.

The insidious nature of frailty is that its onset is so subtle that many of us simply attribute the increasing tiredness and weakness to the natural effects of aging, only to find ourselves caught in a downward spiral before we even realize it. One common experience shared by many in advanced age is the impact of a significant fall. A single misstep—whether on stairs, off a curb, or due to a slippery surface—can lead to an extended period of recovery. Even if full recovery is possible, many never regain their previous level of physical ability, setting off a cascade of reduced activity, increased dependence, and, ultimately, the need for assisted living or nursing home care.

The consequences of a fall underscore the importance of proactive measures. While accidents can be unpredictable, their effects are not beyond our control. Adopting a lifestyle that emphasizes regular vigorous exercise, proper nutrition, and maintaining a positive outlook can help build resilience and mitigate the impact of frailty. By investing in our physical health now, we stand a better chance of preserving our independence and quality of life as we age.

Conclusion

Our journey toward a longer, healthier life is marked by a series of formidable challenges—from early life infections to the chronic diseases of later years and the insidious onset of frailty. Each stage presents its own set of hurdles that can diminish our vitality and independence, yet modern medicine and improved lifestyles have provided us with the tools to confront and often overcome these obstacles. The path is neither straightforward nor inevitable, but it is one where knowledge, prevention, and early intervention make all the difference.

“80% of all deaths are lifestyle related.”

Ultimately, our ability to extend not just our years but our quality of life hinges on a proactive approach to health. Embracing lifestyle changes such as regular exercise, balanced nutrition, and stress management, along with taking advantage of advancements in healthcare, offers us a chance to navigate these challenges successfully. By understanding the nature of each hurdle and actively working to mitigate its impact, we pave the way for a future where longevity is measured not just in years, but in the richness and independence of our lives.

Updated 3/5/2025